Nepalis grow impatient, as their leaders fiddle

A GAGGLE of protesters in Kathmandu, Nepal’s fume-filled capital, want a Himalayan summer to follow the Arab spring. Organised via Facebook, young and dapper professionals meet outside the Magic Beans coffee house to clap, call for a constitution and condemn the wretched performance of their country’s leaders. “Our politics is a kind of a disease,” one of them grumbles.

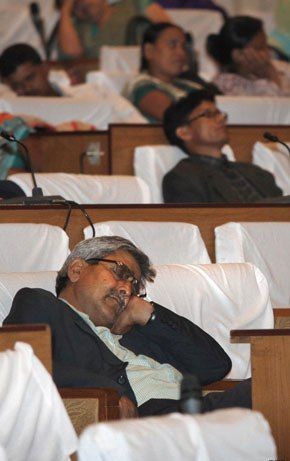

The bankers, lawyers and university students complain that politicians are too busy horse-trading, pocketing public funds or theorising to bother with ruling. It certainly looks that way. Parliamentarians took 17 attempts over seven months merely to vote in a government in February. Then on May 28th they agreed to put off for another three months a much-delayed effort to write a new constitution. As a result, the prime minister, Jhalanath Khanal, who has only just been installed, is poised to quit, restarting the dreary merry-go-round of forming a government.

A diplomat laments that the place has been as good as leaderless for more than two years, as politicians fail to agree on how to run things. Yet matters could be worse. A decade ago a drunk and lovelorn prince wiped out most of the royal family, long a powerful political force, in an after-dinner massacre. And it is only five years since Maoist revolutionaries gave up a ten-year-long rebellion that killed 13,000.

The Maoists remain popular. They swept a 2008 election and retain both a standing army and support among poorer Nepalis. Their demands for social change and for curbing the dominance of a Hindu upper-caste elite through political restructuring (and eventually land reform) form the basis of efforts to draft the constitution. But progress on these scores has been slow. It has taken a constituent assembly two years merely to agree on a name—the “Constitution of Nepal”—to describe the thing it is trying to write.

All the same, profound shifts are quietly under way. The one-time kingdom has become a secular republic, dumping both its authoritarian monarchy and its previous designation as a Hindu state. The Maoists, in turn, have knocked off the sharpest edges of their leftist ideology, and now accept broad liberal values for the constitution, such as the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, competitive democracy and the right to private property.

Just two real sticking-points remain over the constitution. The Maoists want Nepal to have a powerful and directly elected president, whereas much of the political establishment wants the president constrained by a parliament. And, although practically everyone wants a federal system that will devolve powers to local bodies among Nepal’s 30m people, they disagree over the number, and nature, of the new provinces. The Maoists want ten or more, but their opponents, such as the Nepali Congress, insist on fewer, perhaps half as many, to discourage separatism among the country’s 103 ethnic and 93 language groups.

These differences are not insurmountable. Meanwhile, at least Nepal enjoys relative calm. Nobody dreams of a return to war. Nor did the sky fall when United Nations monitors were sent home in January. The main blockage to more rapid political change is a practical one: what to do with the Maoists’ soldiers, some 19,000 of whom still have access to their guns while they squat in camps. Around half will be paid off and sent home (or they will go off to join the millions of Nepalis toiling abroad). The rest will get jobs within a new paramilitary force in conjunction with the Nepali army and police.

The chief question is when. Donors will fund the process, but the Maoist leader, Prachanda (whose real name is Pushpa Kamal Dahal), is hanging on for a big sop. He seems to expect another spell as prime minister, perhaps in time to oversee the next general election, so as to be able to persuade a hardline faction to get behind the disbanding of the Maoist army.

That, in turn, infuriates India. Its diplomats complain of a few thousand gunmen holding up the whole peace process. India hates any idea of pro-China leftists returning to office across the border, especially given its own struggle against Maoist-branded insurgents at home. Yet many Nepalis, even well-heeled protesters in Kathmandu, say they would prefer any government to more stagnation.

They are impatient for Nepal to import the booms enjoyed by the giants on each side, China and India. The local economy plods on, growing at about 3.5% a year (though a vigorous black-market economy goes unmeasured). Some local businessmen claim Nepal is on the threshold of great things. Aid and remittances fuel consumption and a building boom. Since 1980 Nepal has made more gains in education and health (measured by the UN’s Human Development Index) than any other country. Add stability and clearer rules for investors, and money could pour in for hydropower, food production, and services for a young and urbanising population. That sounds appealing—if only politicians would get on with making it a reality.

Source: Economist

0 तपाईंको प्रतिकृया लेख्नु होला ।:

Post a Comment